Bore gauges do not work well for profiling antique flute bores, for the reasons Casey stated, so you need better tools.

I use a set of telescoping T-gauges with extra long handles that allow the diameter of the bore to be measured in

various orientations across the bore. Any discrepancy between the measurements at a particular location along the bore

indicates some kind of distortion, such as ovaling. This can be corrected for by taking several measurements in different

orientations and averaging them. This allows me to find a close approximation of the cross sectional area, which is what

matters acoustically.

Making an accurate map of an existing flute bore allows the construction of a reamer to replicate that bore. Of course,

there are still slight errors in the measurement, so the map is an approximation, and there are errors in the construction

of the reamer and in the effects it has when it is working the wood. But I have noticed that if you are careful, and go to great

lengths to replicate a bore accurately, warts n all, the resulting replica flute sounds very much like the original. It ends

up inheriting some of the tonal character of the original. On the other hand, if you take shortcuts and produce a reamer that

is more regular, the resulting flute sounds considerably different, and often less interesting in its tonal characteristics. This

tells me that it is possible to do the measurements, reamer construction and flute production in such a way as to get a

meaningful result. I’m not claiming that this approach is economic, or commercially viable for someone who makes their

living making flutes, but I am claiming that it is possible, based on the fact that I have actually done it.

I have not yet used any computer modeling though. I’ve just selected good sounding originals and then put a lot of time and energy

into replicating and subsequently tweaking the resulting flutes in order to get what I’m after. That is basically what most flute makers

seems to do, as far as I can tell, although it sounds like there may be some significant differences in how much attention to detail

different people are willing to indulge. I’m willing to indulge a lot, in part because it interests me, and in part because I do

not need to make my living by getting a large number of flutes out the door in a short time period.

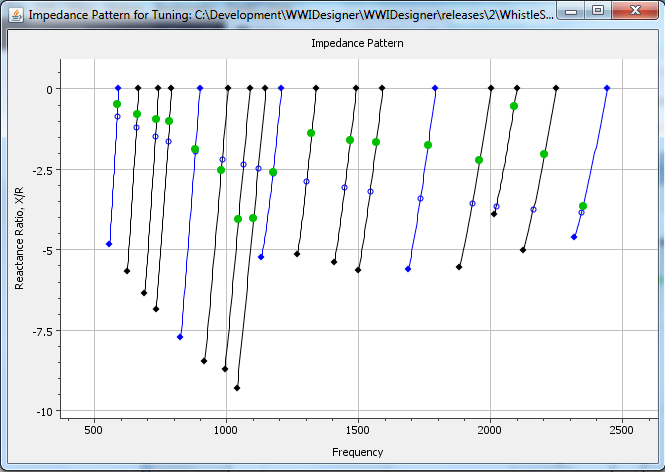

But my interest in a computer modeling approach like the one discussed in this thread goes a bit further. I’d like to know

which of the bore profile irregularities really matter, for good and for bad. For each, regardless of the original maker’s intent, I’d

like to be able to describe precisely what effect it has. I agree that it is going to be a while before a computer model can completely

answer such questions by itself, but I don’t agree with you that this is impossible. I think it will soon be able to allow rapid virtual

prototyping that can inform the process of constructing and testing physical prototypes, and this will ultimately save time.

The modeling technology may not be at that stage yet, but I’ll know when it is at that stage when a computer model can accurately

predict the tuning of flutes that I have in hand. At that stage I will know that it works well enough to be useful to me, and I will be

able to start using it with some degree of confidence, but not over-confidence.

This is basically how science works. It takes a lot of laborious hypothesizing, tool building, and testing cycles, and then you may end

up with something useful. It is not for everyone, but I still like to believe that we live in a society where those who are interested

and willing to put the work in are allowed to continue unmolested.